People enjoying the scenery at Bridal Veil Falls near Provo, Utah, on US 189

An interesting article was brought to my attention recently, which led me down a path to a rather coherent observation about society in general.

I don't generally spend much time if any on Twitter because of the inherent limitations of the platform in actually having a discussion. Still, recently I have seen post after post (on every platform, not just Twitter) condemning what is labeled as "doomism" by a considerable number of climate scientists. Here is a comment from one, Zeke Hausfather, quote:

"It's a bit eye opening how many time[s] I, a climate scientist, have been called a denier in the last 24 hours for having the temerity to say our children are not necessarily consigned to an apocalyptic hellscape of a future.

Doomism is a disease, and a self-fulfilling prophesy."

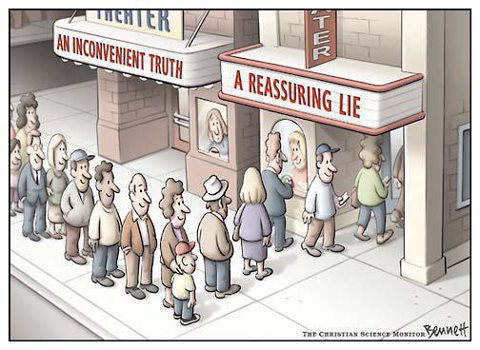

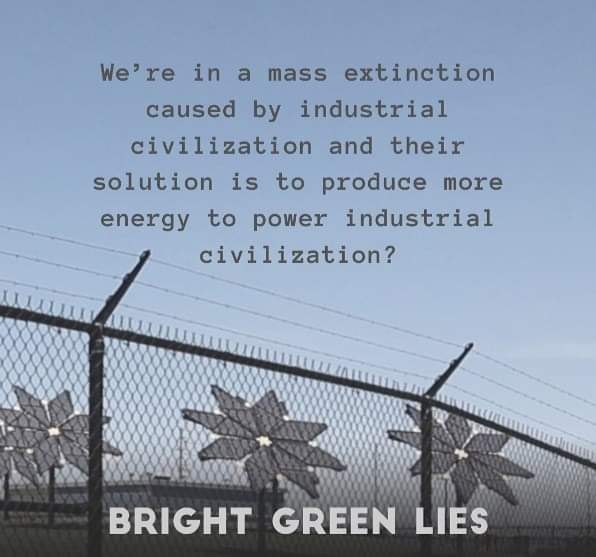

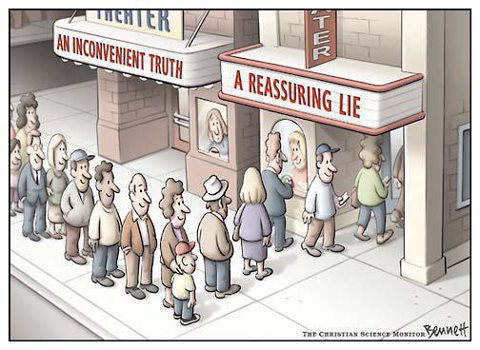

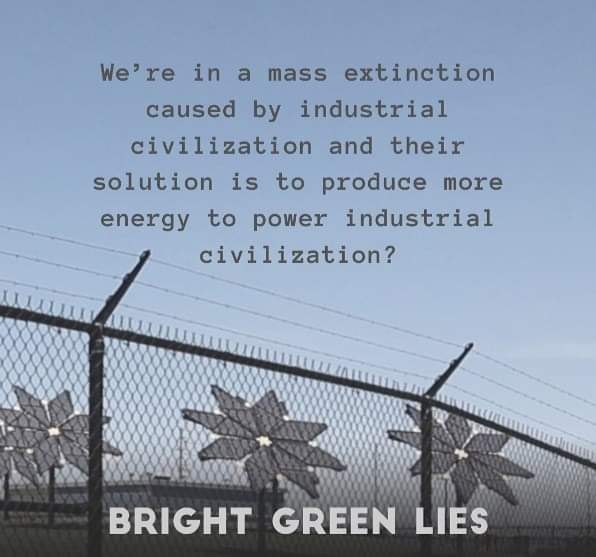

Seriously, I don't know how to take statements like Zeke's. I see it from him, I see it from Michael Mann, I see it from Kathryn Hayhoe, I see it from Simon Clark, and many others too numerous to list. These statements are promulgated from beliefs, not from facts, and as such, they fall into the category of false beliefs, since the scientific proof shows us going in the wrong direction rather than a direction these folks wish we were going in. These people may have a degree in climate science, but where they fall short is a degree in sociology (and I also think many suffer from being energy blind, as Nate Hagens so frequently points out). I think a sufficient number of people agree that climate change is a serious predicament. However, most people lack the knowledge that climate change is caused by ecological overshoot and that carbon emissions are a symptom predicament of overshoot. Climate change cannot be reduced absent a reduction of ecological overshoot, period. We simply lack agency to be able to reduce ecological overshoot voluntarily, so nature will take care of the situation for us. In conclusion, the only real honest summation is that Zeke is, indeed, being a denier, since he is, indeed, suffering from denial. The other psychological issue many people tend to go into is optimism bias, which is why so many well-meaning people think we can do things which in reality are unattainable. More on this part later. This study (which the article above in the first paragraph was based upon) suggests that most people are actually more concerned about the upcoming mass die-off, which is unpreventable due to ecological overshoot, than they are with total human extinction. It also appears to point to fear of living in such a world as being the main motivating factor. This is rather ironic since said world cannot be prevented. I would imagine that this same fear is what motivates so many people to subscribe to so-called "solutions" because the propaganda surrounding those types of ideas offers a reassuring lie rather than an inconvenient truth. So, if one combines these facts into an observation, he or she can clearly see where this fear of living in a world of mass die-off (which is actually already occurring to many different animal and plant species) causes many people to deny the reality and then fall into the optimism bias trap of developing mindsets which lead us in the wrong direction. Two pictures which capture this scenario:

Once someone has fallen into these traps, he or she often fails to realize that what seemed so convincing as a solution just doesn't pass the sniff test when it comes to sustainability.

This study points out that society typically doesn't see predicaments such as ecological overshoot as a hazard of existential risk (which is why so many people focus on symptom predicaments instead). The study more or less shows that the system of civilization itself appears to society to be benign and as a result, most people completely ignore that civilization is a boring apocalypse, quote:

"This article argues that an emphasis on mitigating the hazards (discrete causes) of existential risks is an unnecessarily narrow framing of the challenge facing humanity, one which risks prematurely curtailing the spectrum of policy responses considered. Instead, it argues existential risks constitute but a subset in a broader set of challenges which could directly or indirectly contribute to existential consequences for humanity. To illustrate, we introduce and examine a set of existential risks that often fall outside the scope of, or remain understudied within, the field. By focusing on vulnerability and exposure rather than existential hazards, we develop a new taxonomy which captures factors contributing to these existential risks. Latent structural vulnerabilities in our technological systems and in our societal arrangements may increase our susceptibility to existential hazards. Finally, different types of exposure of our society or its natural base determine if or how a given hazard can interface with pre-existing vulnerabilities, to trigger emergent existential risks.

We argue that far from being peripheral footnotes to their more direct and immediately terminal counterparts, these “Boring Apocalypses” may well prove to be the more endemic and problematic, dragging down and undercutting short-term successes in mitigating more spectacular risks. If the cardinal concern is humanity’s continued survival and prosperity, then focussing academic and public advocacy efforts on reducing direct existential hazards may have the paradoxical potential of exacerbating humanity’s indirect susceptibility to such outcomes. Adopting law and policy perspectives allow us to foreground societal dimensions that complement and reinforce the discourse on existential risks."

Once one comes to the realization that the system of civilization that we (everyone who can actually read this) are all embedded within is unsustainable, it begins to dawn upon him or her that practically everything we do today is unsustainable because of our dependence upon technology use and fossil hydrocarbon energy to power all of that technology.

I shared this (a post with an excerpt from Bright Green Lies in italics) recently with the intro underneath this paragraph, and I think it is really important for people to seriously consider what it is, specifically, that their goals are. Many people have goals which, simply stated, cannot actually be met and most of those goals include keeping things the way they have been for most of our lives. Shifting our priorities away from these unrealistic goals to ones which are actually attainable should be our focus, keeping in mind the principles detailed below.

I constantly see people talk about "saving the planet" or "fighting climate change" or [name your cause here], but how many of those folks have stopped to think about what it is they really want to save? Since civilization is unsustainable, this means that it cannot be sustained: "Things don’t magically appear because it’s convenient for you to think they do. Things come from somewhere. These things require materials. There are costs associated with extracting these materials. Those costs are paid by someone. Even if you really want a groovy, solar-powered mass transit system, the materials still have to come from somewhere [where] someone else lived until their home was destroyed so you can have what you want.

If we want to understand how and why a city—and by extension, an industrial civilization—can never be made sustainable, it would be nice to have a shared definition for WHAT A CITY IS. Not many people (including, ironically, urban planners) understand what a city is or how it functions.

We define a city as people living in high enough densities to require the routine importation of resources. This distinguishes cities from villages or towns which support their populations from nearby lands. (As an extension of this, a civilization is a way of life defined by the growth of cities, among other features such as agriculture, standing armies, bureaucracies, and hierarchies of unjust power.)

As soon as you require the routine importation of resources to survive, two things happen. The first is that your way of life can never be sustainable, because requiring the importation of resources means you’ve denuded the landscape of those particular resources, and any way of life that harms the landbase you need to survive is by definition not sustainable. As your city grows, you will denude an ever-larger area to sustain the city.

Let’s get specific: Where do you get bricks for your city? Where do you get wood? Where do you get food? Where do you get copper for electric wires? Where does sewage go? (Well, in the case of New York City, it used to be dumped in the ocean, but when that was stopped by EPA, New York sent it to Colorado, and now it sends it to Alabama, where, “It greatly reduces the quality of life of anybody that this is around,” according to Heather Hall, the mayor of Parrish, Alabama. “You cannot go outside, you can’t sit on your porch, and this stuff, it’s here in our town.”) Where does electronic waste go? Everything comes from somewhere and goes somewhere. Bright green fairies don’t bring goodies in the night and simultaneously remove All Bad Things.

This is a pattern we’ve seen since the rise of the first city. The pattern is not an accident. Nor is it incidental. This is how cities function.

One sign of intelligence is the ability to recognize patterns. How many thousands of years of cities devastating landbases do we need before we recognize this pattern?

The second thing that happens is that your way of life depends on conquest: if you need this resource and people in other communities won’t trade you for it, you’ll take it. If you can’t take it, or you refuse to, your city will dwindle. This, again, is how cities have operated from the beginning."

So, in the end, doomism is actually nothing like what people like Hausfather, Mann, or Hayhoe would have you believe. It is instead the reality that those people simply refuse to believe. So, they engage in tribalism in a weak attempt to paint those of us who truly comprehend ecological overshoot in a bad light. Knowing that many climate scientists promote technology which can only increase ecological overshoot, it appears rather obvious to me that those who do have not really done their homework and suffer from reductionism. The only strategy that will help is to reduce technology use, not increase it. These folks who label anyone a doomer or someone who engages in doomism obviously suffer from wetiko (colonialism), something I have pointed to as a mental blind spot preventing those who have it from seeing the very features brought to the forefront by the quote from Bright Green Lies above. While there are many books (Paul Levy comes to mind) about wetiko one can learn from, I have found this article about an interview with Russell Means to be one of the most illuminating - plus, it's free!

So, basically, society itself has a myriad of blind spots and mechanisms of denial (especially bargaining) preventing many people from seeing reality. This is also responsible for why we lack agency. I am constantly reminded of this every time somebody says, "Well, if "we" all just do [name of so-called 'solution'], we could turn things around." This is basically nothing more than magical thinking since getting everyone to agree on the same idea is impossible. So the whole if part is the sticking point. Yes, IF we all reduced technology use, we could begin to reduce ecological overshoot. Now, why aren't we all doing this? Hahaha! Exactly - because very few people would agree to undertake such an endeavor. I used to get caught up in these types of ideas myself. Now I comprehend them as hopium. Rather than focus on unattainable ideas, my best advice is to Live Now.

I linked your what is doomism article front page links on https://parracan.org

ReplyDeleteDoomism is something felt or expressed by someone who is not paid a salary that depends on not knowing

ReplyDeleteThis is my little saying for anyone not familiar with "doom"

ReplyDeleteWelcome to the doomosphere,

Enter if you dare,

Because once you know, you cannot unknow.

Welcome to the doomosphere,

the happiest place on the internet!

Excellent! Thanks, Erik

ReplyDeleteI’d like to offer a different interpretation for Manns’ and Hayhoe’s public statements: They know that we are “going the wrong direction”, but their “beliefs” are likely (1)the temperature increase will be more that 2°C, (2) every tenth of a degree over that makes a difference, (3) our goal should be to reduce emissions as much as possible to limit the temperature increase as much possible, (4) were are taking some steps to reduce emissions, (5) if we are “lucky” we can limit the temperature increase to something “tolerable”, (6) but if we publicly state our views, the world will “give up” on reducing emissions and we might end up with an “intolerable” temperature increase, (7) so we must present an optimistic position to the public

ReplyDeleteHi Bruce,

ReplyDeleteWell, we can't reduce emissions until we reduce ecological overshoot, which is precisely why we have ONLY reduced emissions during events which were not under our control which reduced economic activity (recessions, depressions, COVID-19, etc.). More information is in this post: https://problemspredicamentsandtechnology.blogspot.com/2022/05/attention-span-and-role-of-technology.html

Presenting an optimistic position to the public is irrelevant because we lack agency, which is why I point to that article of mine over and over [https://problemspredicamentsandtechnology.blogspot.com/2021/03/agency-do-we-have-free-will.html]. Without sufficient understanding of how society works, one can easily miss this. It really doesn't matter what a person's beliefs are as we are limited by our own psychology. Ask anyone if they are willing to live without external electricity the rest of their life, and keep in mind that as a species we lived without it most all of the last 200,000 years our species has been in existence with the exception of the last 150 years. You will be lucky to find anyone willing - even though this isn't really up to us anyway.

It’s nice to know about this stuff. Thank you. Recently became collapse aware as a college student. I must ask because I’ve seen this from all other groups, is there any toxicity in doomer spaces to be wary of?

ReplyDeleteHi Anonymous,

DeleteLike all human groups, there are always certain elements present. It really depends on how one classifies "toxicity" since that is in the eyes of the beholder. There is what is known as toxic positivity, which works to deny or deflect anything one does not like, so even though initially this might be seen as good, it quickly devolves into an unrealistic element where certain discussions are not allowed. You will also find a wide array of personalities, some of which you may not agree with.